Richard Dawkins, like his intellectual ancestors David Hume, Feurbach, Emile Zola and countless others, claims not to be religious. In saying so, more times than I care to count, he is not being entirely honest, for whether Dr. Dawkins realizes it or not, Man by his very nature is a religious being. Aristotle claimed that Man was a rational and, therefore, a political, animal (and therefore one could not escape thinking and,alas, politics). The Church goes further, and declares that Man also cannot avoid the fact that he is religious.

Richard Dawkins, like his intellectual ancestors David Hume, Feurbach, Emile Zola and countless others, claims not to be religious. In saying so, more times than I care to count, he is not being entirely honest, for whether Dr. Dawkins realizes it or not, Man by his very nature is a religious being. Aristotle claimed that Man was a rational and, therefore, a political, animal (and therefore one could not escape thinking and,alas, politics). The Church goes further, and declares that Man also cannot avoid the fact that he is religious.

Religion, derived from the Latin verb ligare, to bind or to fasten, may be defined in a broad sense as those a priori principles, whether explicitly declared or not, to which we are bound, that guide our actions. Dawkins would not admit that he is religious, by which he would presumably mean that he is not bound to a revealed (particularly Christian) religion, requiring adherence to a divine being. He would call his principles a ‘set of values’ or a ‘hierarchy of goods’. But, call it what he may, he still has a ‘religion’, all those things he believes that guide what he does, how he thinks, what he teaches, and what he writes.

Take, for example, Professor Dawkins’ recent tweet that it is immoral to bring a Down’s Syndrome baby into the world; rather, he said, the only moral thing to do when a mother receives such a diagnosis is to abort her child. Dawkins has received much backlash for his post, but he is simply acting on his religious principles (and reiterating in a more dogmatic way what most people already do in practice).

Although not always the strongest impulse in Man (our passions are often more powerful!), religion is the most fundamental (excuse the pun), in the sense that everything we do is ultimately guided by our religion. One’s religion need not be explicit: One can adopt hedonism, wherein the pursuit of pleasure becomes the guiding principle, or self-worship, or Communism, or Christianity, Buddhism or Islam.

As the source of all that Men do, religion is a force of the greatest good, or the greatest evil. As the Roman poet Juvenal wrote, corruptio optimi pessima, the corruption of the best is the worst. Since evil is nothing more than a privation of good, that is, something ‘missing’ in an already existing good, the more good something has, the more capacity it has for evil. After all, in tribute to fellow sci-fi geeks, Darth Vader would not be menacing if he were three feet tall dressed in pink. And, on a more realistic note, Satan is only so evil because he is, or was, so good.

That is also why our choice of which religion to adopt and follow is the most important decision we can make in this life. We should keep in mind, for those inclined to an agnostic insousiance, that not to choose is itself a choice, for even indifferentism, the philosophy of ‘who gives a rat’s behind about anything at all’, is a kind of religion. So it is incumbent on us to choose our religion wisely.

Most of us make this choice at some point in our journey to adulthood. Will we adopt religion (the principles) of our parents? Or go off on our own, for good or ill?

It makes sense that if God does exist, and exist He must, then He would reveal the religion that is most conducive to our own good as human beings. This we call the ‘true religion’, for, by the nature of truth (specifically, the principle of non-contradiction, to which even God Himself is ‘bound’), religions cannot contradict one another, and still both be true. Either Christ came in the flesh, or He did not; either the priesthood and Eucharist are real, or they are not; abortion is either murder, or it is not, and so on.

Of course, most faith groups on this planet claim that God revealed their religion but, ultimately, only one of them can be true. The rest will be, to a greater or lesser extent, either missing some truths, or outright false.

The more false principles the religion contains, or the more truths missing from the religion, the more evil it can be. The ancient Canaanites believed in sacrificing children as part of their religions ceremonies. Reason tells us that this is evil, and cannot be tolerated in a society; in fact, such practices are, to put it mildly, counter-productive to any society. Hence, their religion, at least to that extent, was evil. In fact, it was so evil that God decreeds its eradication.

Pope Leo XIII wrote in his landmark encyclical Immoratale Dei in 1885 that there are many signs which point to the true religion, insofar as it accords with human nature, our own happiness, peace, concord, the moral law and so on. Of course, the Holy Father believes, as do I, that Catholicism is the true religion. A hundred or so years later, Dignitatis Humanae taught that this one true religion subsists in the Catholic Church, and that other religions are true insofar as they share the truth of the Church.

What we are witnessing now in the world is the corruptio religionis, the corruption of religion itself, which leads to great evil, for no evil is done more willingly than that done in the name of religion. But this is not entirely new. Under Henry VIII’s Tudor reign, those deviating from his understanding of religion would be put to death by hanging, drawing and quartering, the gruesome details of which probably could not be described in this post (well, I suppose I am my own censor, but you, dear reader, can look it up). There was also death by ‘pressing’, wherein a heavy door was placed on top of the prone victim, with a sharp stone under his back, and bigger stones placed gradually on top of the door until suffocation ensued; sometimes onlookers were permitted to jump on top for a quicker, more mericful death. See the martyrdom of Saint Margaret Clitherow, a mother and wife, for details.

Of course, in Tudor England, and in current varieties of Islam, violating the religion of the State was seen also as an act of treason, but the point is still taken. For then the State becomes, to some degree, one’s religion. We see the culmination of the ‘State as religion’, ironically, in the atheistic and purpotedly non-religious Communist regimes, the mountain of whose evils are nigh-indescribable.

So, great evil can be done in the name of the religion, but religion is also the source of the greatest good. Most of the good principles that our individual and societal conduct are from the Judeo-Christian religion. But, alas, we are losing our own conviction in the truths of these principles, and it is generally when we are acting contrary to our principles that we act half-heartedly.

I don’t really think that Dawkins and company really, deep down, believe some of the things they say. I really do hope they have elements of Christianity at heart, or at least someday will so have. In his ravings, Dawkins seems in particular to ‘protest too much methinks’. Perhaps he is trying to convince himself most of all of the ‘God delusion’…

The fanatics with ISIS are another story, for the scary thing is that they not only believe infidels should be mercilessly killed, but are quite willing to carry out the deed. That is why Chesterton said that religion really is the only thing worth fighting for. Religion decides not only the course of the world, but, more importantly, the fate of each individual soul, for good, or for evil.

August 25, 2014

King St. Louis IX, St. Joseph Calasanz

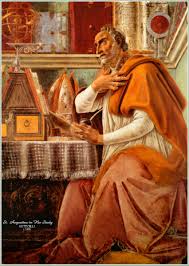

Sero te amavi… “Late have I loved Thee, O beauty ever ancient and ever new…”

Sero te amavi… “Late have I loved Thee, O beauty ever ancient and ever new…”